New paper in Nature Communications: Ismaeel et al. (2024) Patterns of tropical forest understory temperatures.

It’s a thing we do at SoilTemp: create microclimate maps over large extents for all to use. We have done this before for soil temperature at the global scale (with 1 km resolution), and have done so for European forest understory temperatures at a breathtaking 25-m resolution.

And now we do that again! This time, for an area that has long been undersampled, but that is extremely important for global biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: tropical forests. As is the case for European forests, we can expect substantial temperature buffering under tropical forest canopies. How much, that has always been hard to say.

Not anymore, as we are proud to introduce a new paper in Nature Communications: patterns of tropical forest understory temperatures. The big thing: we created maps of tropical forest understory temperatures at a resolution of just a few tens of meters for all tropical forests, in South America, Africa, and Oceania!

As expected, forest understories were on average cooler (1.58°C, to be precise) than macroclimatic temperatures, and they were also buffered more (1.72°C lower diurnal – day/night – variation) than macroclimate.

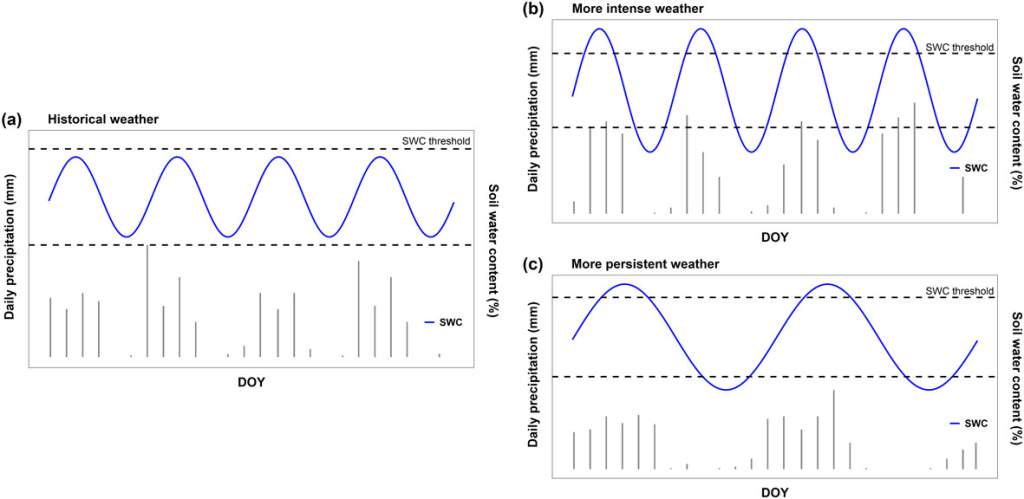

Importantly, however, these averages hide significant spatiotemporal variation in that buffering, driven by patterns in macroclimate, vegetation structure, and topography. This variation holds some important information for understanding of these important ecosystems. For example, temperature buffering is stronger in regions with a distinct dry season. Although reduced rainfall is usually associated with higher temperatures, deep-rooting tropical species can for a long time still access water reserves and keep up their ‘airconditioning’ function, effectively creating a larger difference between understory and free-air temperatures.

The former works as long as these droughts remain within reasonable limits, of course, as climate change might very well push these forests over a threshold, making them lose their airconditioning function and rapidly increasing understory microclimatic temperatures. But that’s a story for another day.

An interesting observation for me is the fact that offsets across these tropical forests are usually not so large. On a daily basis, forest understory temperatures were often less than 1°C cooler than macroclimatic temperatures outside the forests. This was especially true in Indonesia, for example, but large swaths of South American and African rainforests are showing surprisingly small offset values as well.

This phenomenon can be attributed partially to the contrast between daily maximums (which tend to be cooler in forests) and minimums (warmer within forests). However, there might be other contributing factors at play. The high humidity prevalent in tropical regions is likely another significant influencer, dampening the intensity of microclimatic differences.

Nevertheless, despite these seemingly small variations, the consistent stability of temperatures throughout the year results in a cumulative effect. Over time, these incremental differences in temperature do add up, significantly impacting the overall energy input within the ecosystem.

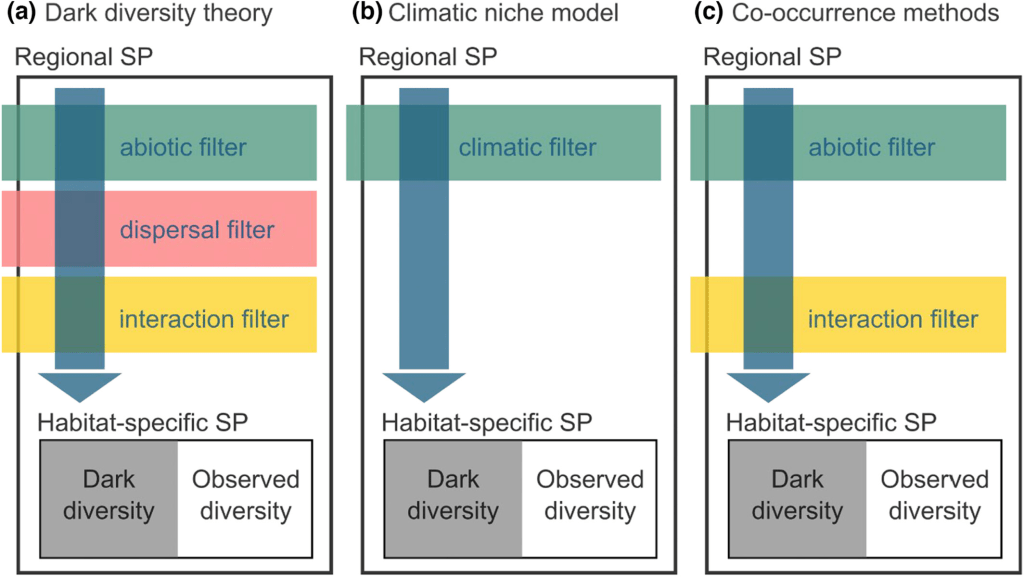

The marked disparities and the crucial spatial diversity present across the pantropical regions underscore the significance of the maps we’ve crafted. These visual representations hold immense importance for anyone delving into the intricate workings of tropical forest understories, spanning from deciphering species distributions to comprehending litter decomposition dynamics. The relevance of such high-resolution microclimate products has already been elegantly demonstrated in understanding the distribution patterns of European forest understory plants. It’s only a matter of time before their paramount significance in tropical ecosystems is similarly illuminated.

The maps are freely available here! For now, at a 300 m-resolution, while we figure out a good way to share the 30-m resolution files open access. The latter are currently available upon request.