Non-native species can be, pardon my words, a hell of a nuisance sometimes.

Case in point: invasive pine species in the Southern Hemisphere. Did you know that there are no (none!) native pine species south of the equator? Given how common pines are here in Western Europe, I always found that hard to fathom. But given how common they are in the Southern Hemisphere, it becomes downright mind-boggling.

For over a century, pines have been among the most widely used genera in plantation forestry across many Southern Hemisphere countries, including Chile and Argentina, but also South Africa and New Zealand. The problem is: once they’re there, they start spreading. And many types of native vegetation – such as the iconic Araucaria forests of Chilean Patagonia, or the grasslands of the Patagonian steppe – are highly vulnerable to pine invasion. You can almost see the invasion front creep forward.

Even worse, once they’re established, these pines are devastating for native biodiversity. They grow into complex, tangled forests that are extremely hard to get through (“unleashed” pines don’t need straight lines anymore – let alone straight stems). They acidify the soils and smother out the light, resulting in near-deserts underneath their needly branches.

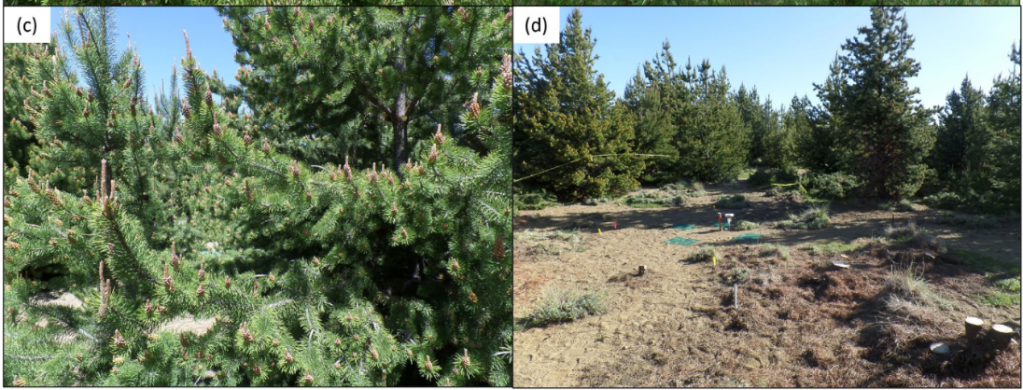

For nature conservation in places like Patagonia, this is a nightmare. And to make matters worse, it’s pretty tough to get rid of them once they’re established. When I had the opportunity to visit Malalcahuello National Reserve in central Chile (home to the famous ‘monkey puzzle tree’ (Araucaria araucana) forests), I got to see the trouble in action. Pine removal is simply a lot of manual labour, and the end result is far from pretty.

But when they’re gone, they’re gone, right?

…Right?

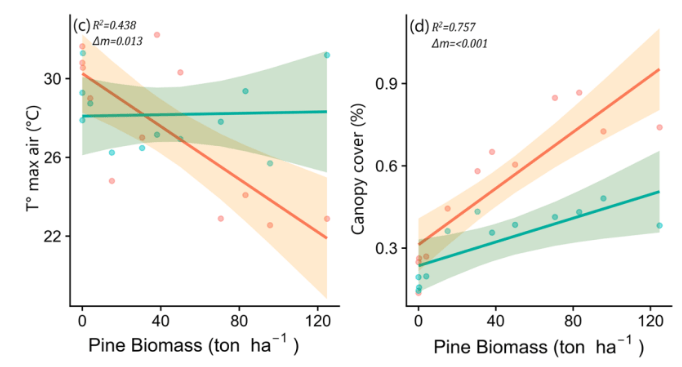

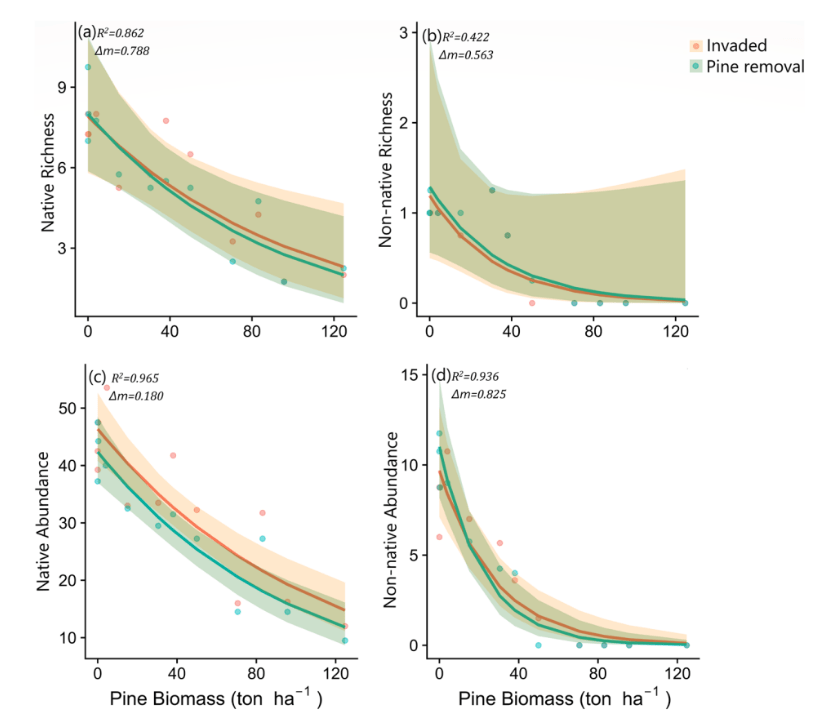

That’s exactly what we set out to test in a paper just published in the Journal of Vegetation Science, led by our colleagues from the University of Concepción in Chile. From previous work, we already knew how bad pines are for native ecosystems: they significantly reduce the richness and abundance of native species, and cause major changes in microclimatic conditions (air and soil temperature) and soil properties (reductions in nitrogen, potassium, and pH). The big question was: do those systems recover after pine removal?

First, a little good news. Yes, we did see a recovery of microclimatic conditions to levels close to uninvaded control sites, driven by the reduction in pine canopy cover and litter. But… that’s where the good news ended.

We also looked at how native understory diversity responded to pine removal, two years after the intervention. The result? It didn’t do shit. The desert remained just as deserted after pine removal as it was before – especially in the sites that had been most heavily invaded.

This tells us that the legacy effects of pine invasion are strong, at least up to two years after removal. If anything bounced back at all, it was pine seedlings. Native species barely benefited from the improved microclimate conditions.

So is this a gloomy story?

Yeah – maybe this time it is.

But that doesn’t make it any less important. It’s crucial to know that some conservation problems are simply a pain in the ass. At least now we know, and we can keep searching for better solutions. Our paper suggests that effective management of invasive conifers must move beyond tree removal alone, and include complementary restoration actions that address persistent abiotic and biotic legacies.

And perhaps this is, once again, a warning: if you can prevent those pines from establishing in the first place, it’s a whole lot cheaper (and far less annoying) than trying to get rid of them later.

But that’s a different story altogether. Because first we need to know which species to act on before they become annoying… and that’s simply not how we humans tend to work.

Reference

Fuentes-Lillo et al. (2026) Beyond Control: Short-Term Legacy Effects of Invasive Nonnative Trees May Halt Biodiversity Recovery. Journal of Vegetation Science. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jvs.70110