Imagine: it’s a hot summer day. You’re sweating away in an urban apartment. Perhaps ice-cream would come to mind, or a dive in a swimming pool. Or a nice stroll through a lush and cool summer forest. Yes, that last one could be a great solution as well: forest microclimates contrast strongly with the climate outside forests, and on a bright summer day that difference could be up to several degrees Celsius. However, the climate inside forests is significantly more complicated than simply this air-conditioning on a hot summer day. Nevertheless, it is crucial for the understanding of the biodiversity and functioning of our forests to get to this true forest microclimate and integrate it into our ecological research.

Despite the potentially broad impact of this microclimate on the response of forest ecosystems to global change, we have long lacked a good idea of how microclimates within and below tree canopies drive nature’s response to global change. Recently, however, the importance of microclimate has moved firmly into the spotlights (see e.g. Zellweger et al. 2020, Lembrechts and Nijs 2020), and our understanding of what climate means below our forest canopies has been rapidly increasing.

With a team of (forest) microclimate experts, we decided we’d have to sit together and ‘take the temperature’ of what we know and what we don’t about forest microclimates. We met in a beautiful mansion in the middle of Sweden during a winter snowstorm in late February 2020 (for many of us the last time we got another view than our own home office as soon after the world got into lockdown). In that inspiring atmosphere, we discussed our current knowledge on forest microclimate and set a first step towards a paper summarizing that knowledge. That paper is now out for all to read!

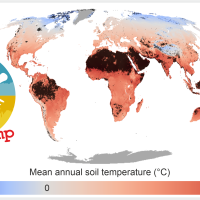

In this review paper, we explain how variation in forest microclimates over space and time results from an interplay of forest features, topography and landscape composition. We stress and exemplify the importance of considering forest microclimates to understand variation in biodiversity and ecosystem functions across forest landscapes. Next, we explain how macroclimate warming (of the free atmosphere) can affect microclimates, and vice versa, via interactions with land-use changes across different biomes. We summarize all drivers of forest microclimate to provide a good idea of the many factors at play and how they are influencing the outcome (as shown in the figure below).

Finally, we wanted to know what had to come next. With all those present at the meeting in this beautiful and peaceful Swedish mansion, we did a priority ranking of future research questions at the interface of microclimate ecology and global change biology. We realized progress was needed (and luckily soon to be expected) on three key themes: (1) disentangling the drivers and feedbacks of forest microclimates; (2) global and regional mapping and predictions of forest microclimates; and (3) the impacts of microclimate on forest biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in the face of climate change.

We end with a very positive note: good microclimate data is increasingly becoming available (see e.g. Lembrechts et al. 2020), opening the door to accurate and trustworthy models of climate variability at spatial and temporal scales relevant to our forests. This will revolutionize our understanding of the dynamics, drivers and implications of forest microclimates on biodiversity and ecological functions, and the impacts of global change. Yet this data is coming not a minute too late, as it is urgently needed to support the sustainable use of forests and to secure their biodiversity and ecosystem services for future generations. Together, and with good data at hand, we can make that last point a reality.