A warmer climate of origin does not necessarily protect exotic plants from heatwaves like our country has experienced in recent summers, we showed in a recent paper by Charly Géron, PhD candidate in our group. What does? Local microclimates!

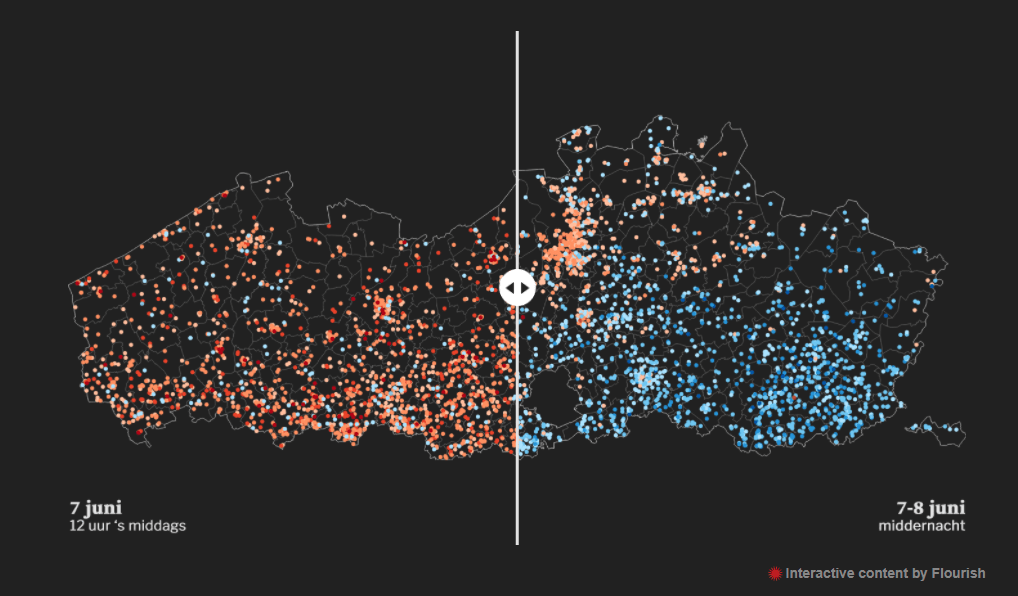

Our cities have an increasingly rich diversity of alien plant species. In particular, species from native regions with warmer climates tend to thrive in the city, where they can benefit from the so-called “urban heat island effect”, in which our cities start to be several degrees warmer than the surrounding countryside. A recent study by the university of Ghent and the royal meteorological institute of Belgium (Steven Caluwaerts and colleagues) has shown that the temperature difference between city centre and rural country side added up to as much as 6 °C during the heatwave of summer 2019.

“We already knew that exotics from warmer regions prefer our cities because of that warmer climate,” Charly Géron, lead author of the study, explains. “The question remained whether these species would also cope better with heat waves in urban settings in summer, as we knew that the impact of heat waves in the city can be much harder.”

So now it turns out that those warm-adapted species don’t necessarily have an edge in the city during a heat wave: they too see their stress levels go up. At least, if they are in full sunlight. Both species of warm and cold origin responded mainly to local shade effects: growing in the shade no matter if it is due to trees or buildings, allowed them to keep their stress levels under control. However, in unshaded city or countryside open spaces, their stress levels increased.

“These findings tell us that the effects of urban heat islands on plants are not as straightforward as thought,” explains Géron. “Although those warm species probably benefit from the warmer winter temperatures in the city (you also have much less ice-scratching to do if your car is parked in the city than in the countryside, because the heat island effect protects against freezing temperatures) or also the longer growing season (earlier and later favourable periods in cities with milder temperatures), for those extreme temperatures during a heat wave, it is mainly the local shade effect that counts.”

Similar patterns also show up in the dataset of the citizen science project “CuriousNoses in the Garden”, says Jonas Lembrechts, scientist in the latter project. “We see clearly that local factors such as shading by trees or buildings can do wonders for maximum temperatures in our city soils, a cooling effect from which those plants can also benefit. At night or in winter, those local effects play much less of a role: the city as a whole heats up due to the release of heat by the urban structures, whether or not there is a lot of shade nearby.” This contrast between local shading effects during the day and urban heat islands at night that CuriousNoses’ citizen scientists observe now appears to have an impact on the success of non-native plants as well.