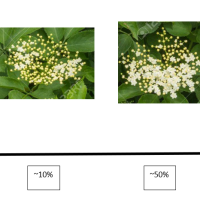

A few weeks ago, the journal Annals of Botany asked me to write a commentary pieceon a new paper coming out on the effect of climate change on grass species on a subantarctic island. An intriguing paper, as they compared the response of native and non-native grasses to climate warming, a thread that we see rapidly unfolding in front of our eyes, especially in such cold environments.

Their findings? The species with the greatest rate of spread over the last decades – the non-native, warm-adapted newcomers – showed much higher adaptability to cimate change than their native counterparts.

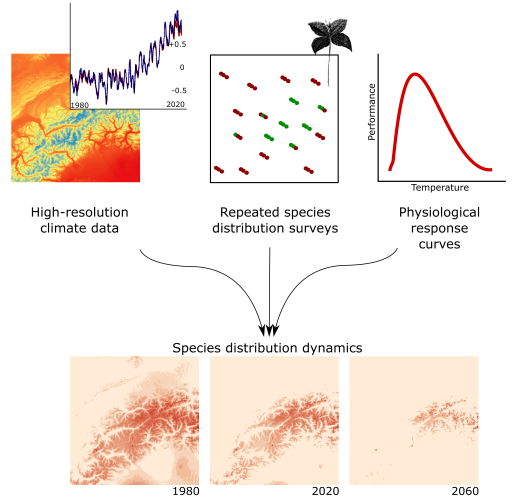

What I found most interesting about this study – and what triggered me to write this Commentary piece – is that it elegantly highlights the new ways in which we will have to do ecology from now into the future, a new way that pivots around what I would like to call ‘the holy trinity of spatial climate change ecology’. This ‘holy trinity’ is the type of data that we need to tackle this rapidly accelerating problem, before it is too late: 1) high-resolution environmental data, 2) long-term biodiversity monitoring and 3) physiological experiments.

Vegetation monitoring in extreme environments – here in a volcanic landscape at high elevations in the Andes

In this commentary paper, I argue that, when collected in tandem, on large scales, at high resolutions and in interaction with each other, these three data types can provide the critical baseline data to answer questions on why species are moving and adapting, and predict their fate in a rapidly changing future. And while all three are advancing rapidly in these times, it is in their interaction that most merit can be found.

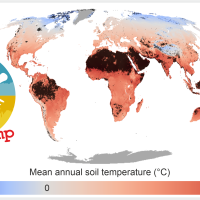

The holy trinity of spatial climate change ecology: if we have 1) high-resolution climate data (both in space and over time), 2) long-term species distribution surveys and ideally 3) the actual performance of the organism as a function of the climate, we can model their distribution in past, present and future.

Indeed, as biodiversity starts to react more and more to these accelerating climate changes, we need long-term biodiversity data, linked with high-resolution climate data from there where it matters for the organisms. Strengthening them even further with physiological experiments on how these organisms actually react to said climate, allows stepping away from correlative models only and build those models on known mechanisms. The latter can give those future predictions the extra credibility they need.

It is thus the integration of these three data types that will allow climate change ecology to move forward. And that is exactly what we should be aiming for, if we want to tackle the complex and multi-dimensional issues of biodiversity conversation under accelerating global change, as the rate of change demands rapid understanding of and action on species (re)distributions.

Ecological fieldwork in the dry Andes, Argentina

Further reading

Lembrechts JJ, The Holy Trinity of spatial climate change ecology: high-resolution climate data, long-term biodiversity monitoring and physiological experiments. A commentary on: ‘Invasive grasses of sub-Antarctic Marion Island respond to increasing temperatures at the expense of chilling tolerance’, Annals of Botany, Volume 125, Issue 5, 8 April 2020, Pages ix–x, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcaa057

What about interactions of the effect of changes in the species with other factors in the environment? Like how would the change in grass composition affect the herbivores there?

Is that a subset of the biodiversity data?

Thanks for your comment! I fully agree that biotic interactions are critical as well. This could be contained within the biodiversity data, indeed – yet it is of course tricky to capture all organism groups in a longterm survey (animals, plants, microbes…)