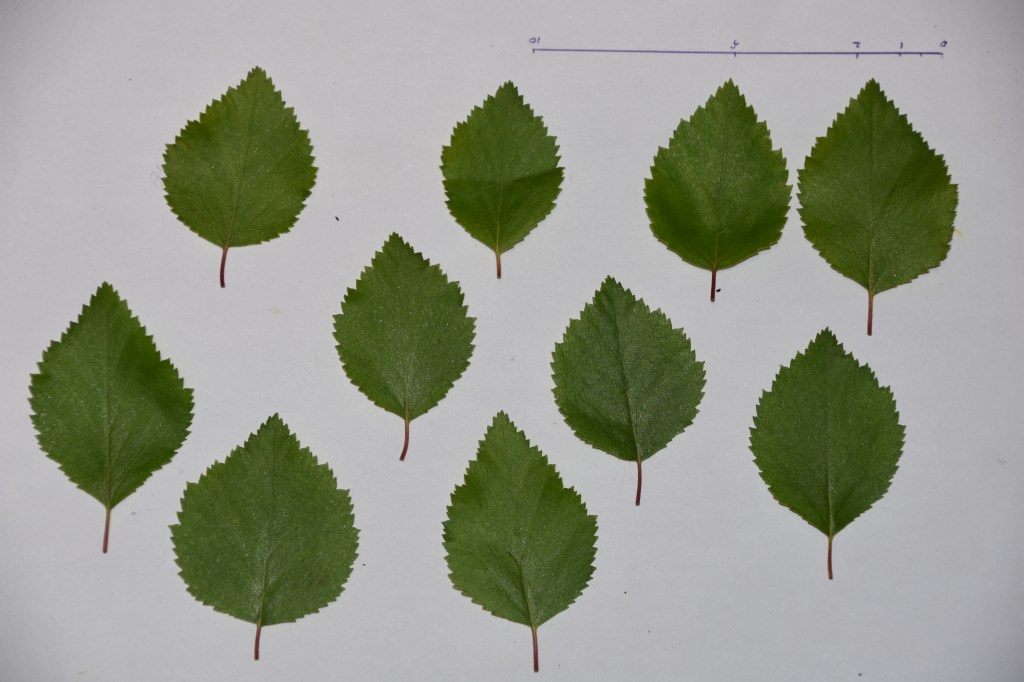

In 2016, a significant endeavor began as we initiated the monitoring of vegetation along two cherished mountain trails in the Abisko region. Our primary objective was to assess the impact of these trails on the mountain vegetation. Specifically, we had a hunch that the trails might induce similar effects to what we had observed along roads: a notable reshuffling of mountain plants, allowing species to travel up and down the mountain, following the footsteps of hikers on the trails.

Understanding changes in species distribution becomes much smoother when tracking the same plants over an extended period. Therefore, it required persistence. With some resourceful juggling of funds and time, we succeeded in assembling the necessary crews to revisit these trails in 2018 and 2020 (though we have to admit, Covid almost thwarted our plans!).

Now, in 2023, our team has returned, fully recharged and eager to embark on another year of monitoring. To add to the excitement, we’ve welcomed new master students to our ranks, two of whom will delve into the intriguing topic of how these trails impact the vegetation.

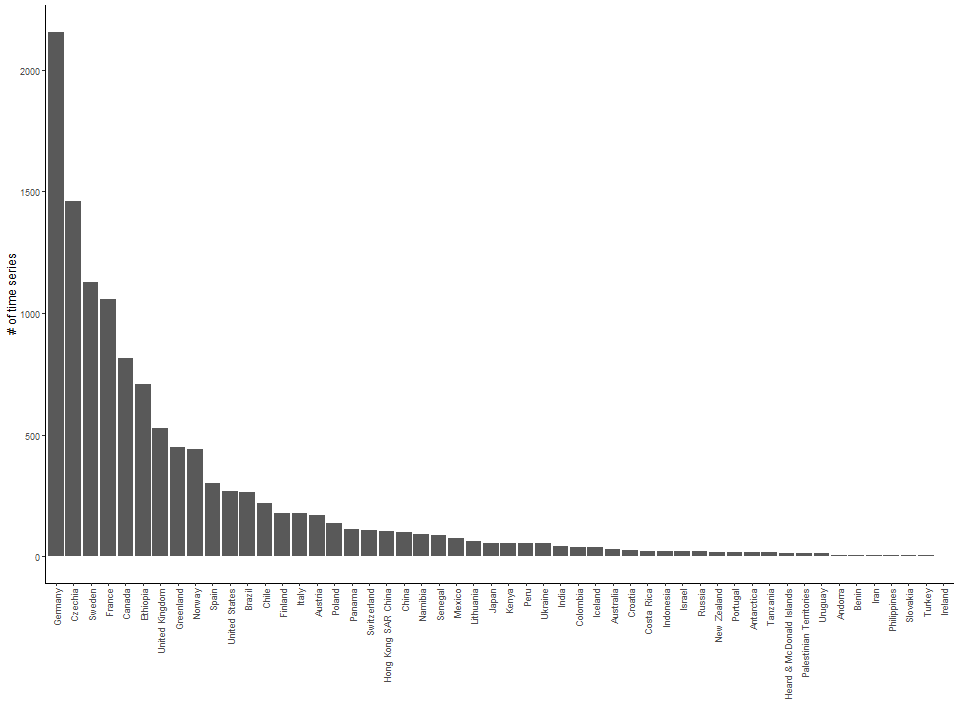

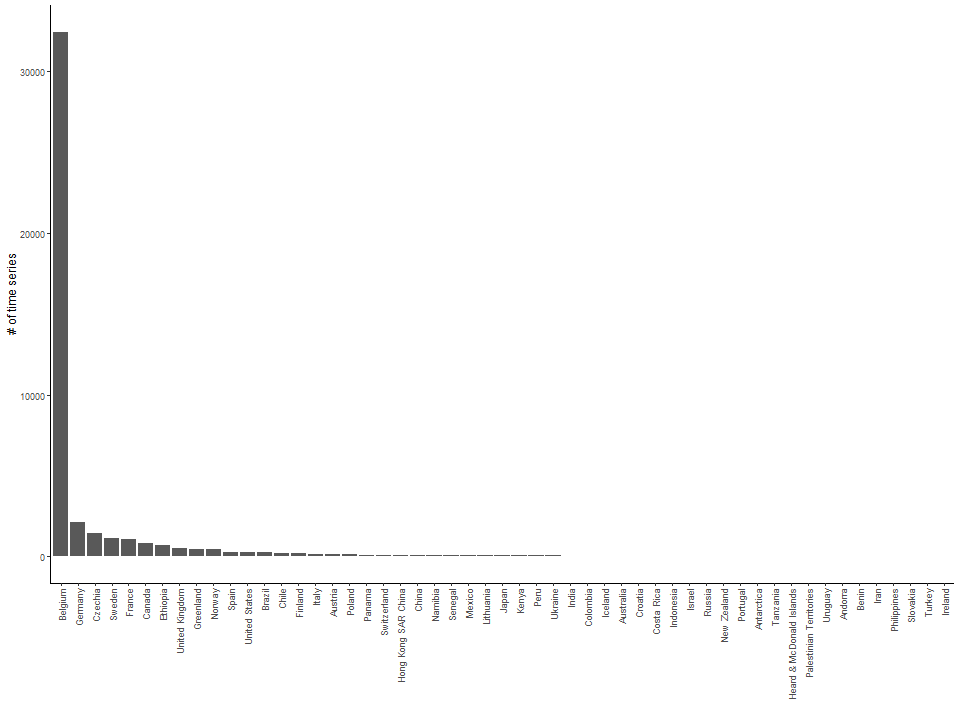

Tist will focus on the temporal dynamics, paying close attention to non-native species. We already know that non-native species tend to thrive near trails worldwide, although perhaps not as fervently as they do near roadsides. In the northern Scandes, however, these non-native species seem to have been limited along the trails so far, possibly due to the extremely cold climate and the comparatively lower number of non-native species in European mountain regions. Nonetheless, such circumstances can change rapidly, which is why Tist will diligently monitor their movements: Are they reaching higher elevations in 2023 compared to 2016? Is their coverage increasing?

Meanwhile, Violetta will be investigating belowground, focusing on the crucial organisms known as mycorrhizae. We wonder whether our trails are affecting the mycorrhizal communities to a similar extent as roads do. The prevailing idea is that the impact on these communities will be noticeable but less intense than that observed along mountain roads due to the trails’ lower disturbance levels.

Let the journey of discovery begin! Until then, our team will traverse those beautiful slopes in pursuit of botanical wonders, eager to unravel the secrets that lie beneath the canopy.