We ecologists and biogeographers all want to know so badly where species are and are not living. This quest lies at the very heart of our discipline, as it provides invaluable insights into how global changes are impacting biodiversity across the planet. For this quest, we are relying on a vast array of models collectively known as ‘Habitat Suitability Models’ (HSM), which serve as our guiding compass in predicting exactly that.

Now, while there are countless ways to improve (or screw up) those models, their efficacy ultimately hinges on the quality of data we input. This, in itself, presents its own set of challenges. Here in this story, we delve into one pivotal problem concerning this data, in light of a new paper (Da Re et al. 2023) that just came out in Methods in Ecology & Evolution (MEE).

The crux of the matter lies in the fact that it is considerably more straightforward to determine where a species currently resides than to pinpoint where it does not. Many of the easiest methods for recording species observations, such as the popular iNaturalist app, primarily furnish information about where species are found.

However, the shadowy realm of where a species is absent poses a greater challenge. To ascertain the areas devoid of a particular species, more intricate monitoring techniques become necessary. These techniques often involve the establishment of vegetation monitoring plots, which allow scientists to systematically survey an area and deduce the absence of the species of interest. Nevertheless, even with these more labour-intensive tools, certainty in declaring the absence of a species can remain elusive – but that’s a separate story in its own right.

Distribution models need ‘absences’ to run, however. Thus, in situations where actual absence data from the field is scarce, a common practice is to generate what are known as “pseudo-absences.” Essentially, this entails selecting a set of locations where a species was not observed and treating them as surrogate absence points. However, the pivotal aspect we address in this story today is that the method used to choose these pseudo-absences can significantly impact the quality of your model.

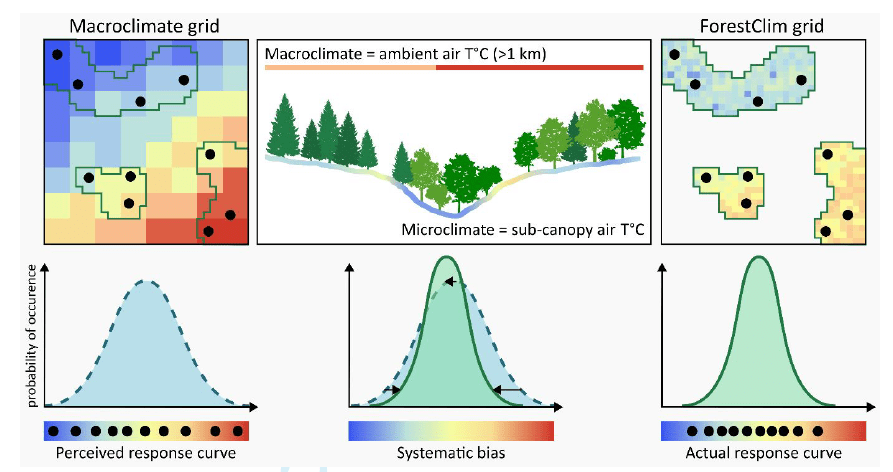

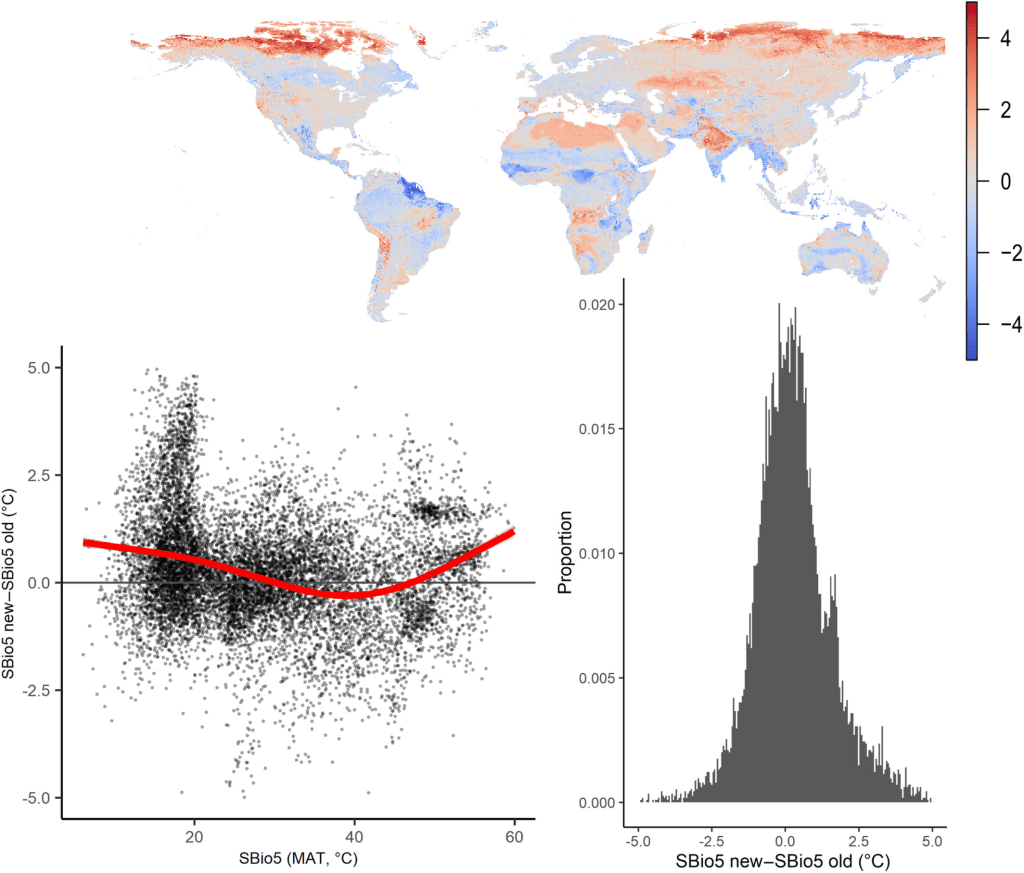

In our recent paper featured in MEE, we introduce a new way to select these pseudo-absences: not just randomly in space. Instead of a haphazard geographical selection, our method, termed the ‘uniform’ sampling approach, strategically identifies absence points in the environmental space.Why? The rationale behind the approach lies in the fact that HSMs explicitly link species observations to environmental conditions (e.g., climate) to predict where a species can and cannot be. Importantly, these environmental variables often exhibit a non-random distribution across the landscape.

For example, let’s consider a scenario where the climate exhibits remarkable homogeneity across vast lowland areas but presents steep gradients in mountainous terrain. If one were to randomly select points in such a landscape to gather pseudo-absences, there would be a disproportionate oversampling of lowland climatic condition. Consequently, this could lead to a skewed dataset, ultimately compromising the accuracy of the resulting Habitat Suitability Models (HSMs).

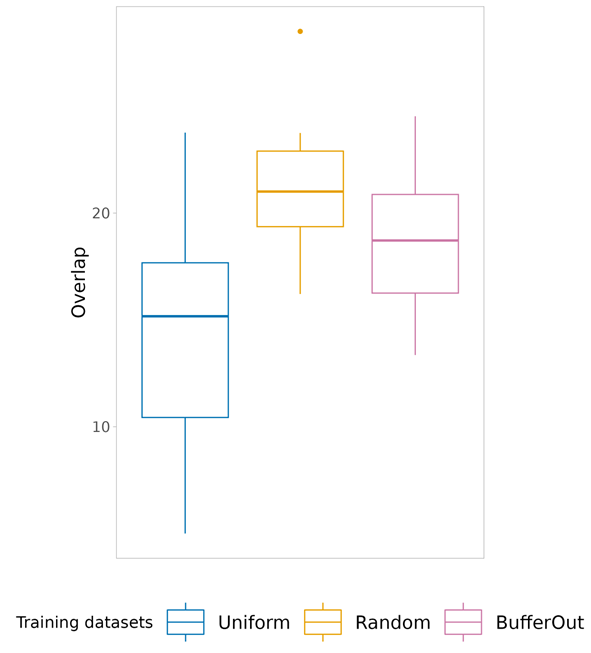

Sampling the absences across the range of climatic conditions instead, as we propose here, serves as an effective remedy to this sample location bias (i.e., sampling is skewed towards the most prevalent habitats within the geographical space, as observed in the example mentioned earlier) and reduce so-called class overlap (i.e., overlap between environmental conditions associated with species presences and pseudo-absences).

Easy to say that, of course, but in that freshly published paper we (or mainly: Daniele, Enrico and Manuele, the smart minds behind the paper) put these ideas to the test. The findings resoundingly endorse our approach: the ‘uniform’ environmental sampling method significantly reduces sample location bias and class overlap without sacrificing predictive performance. As such, it ensures that we can gather pseudo-absences adequately representing the environmental conditions available across the study area.

Importantly, we go further than just sharing those insights. We also provide an R-package with the essential functions to implement the Uniform sampling method in your own workfloy. So, if you find yourself grappling with the challenges posed by presence-only species observation data when fueling your models, we encourage you to explore the new ‘USE’-package to collect a fair bunch of pseudo-absences!