Some papers just hit harder than others. And this latest one – just out in Molecular Ecology – sits right at the top of the epic scale. The topic? The impact of mountain roads on plant-fungal interactions.

Here’s the thing: we’ve been looking at the effects of mountain roads for years – since 2007, in fact, when the first surveys of the Mountain Invasion Research Network (MIREN) kicked off. And over time, we learned a lot: changes in plant communities, upslope and downslope shifts in distributions, effects on functional traits – you name it. But one thing remained a mystery: what was going on belowground.

So, we decided to go digging. Literally.

We set out with an ambitious plan: sample roots from long-term MIREN plots – both roadsides and adjacent vegetation, across elevation gradients and multiple regions. The goal? To understand how root-associated fungi respond to road disturbance, and whether these patterns shift with altitude or across continents.

Solid idea, right? But then came the execution.

Enter the epic field trips: Norway, Chile, Argentina. Samples flown in from Tenerife and the Czech Republic. Sorting root samples. Washing them. Cutting them into tiny pieces. Amplicon sequencing to reveal the fungal communities hiding inside. Add in a freezer disaster that cost us an entire region’s worth of samples (yep, that happened!), and then the analytical rabbit hole: plant species, fungal species, interactions, co-occurrence patterns… A deep dive into Joint Species Distribution Modelling to figure out what we can and cannot tease apart from this complex mess.

Honestly? Easily the most time-consuming paper I’ve worked on so far. And that doesn’t even count the countless hours of meticulous, patient work by first author Dajana – without her expertise in soil microbial ecology, this paper simply wouldn’t exist.

But oh boy, was it worth it.

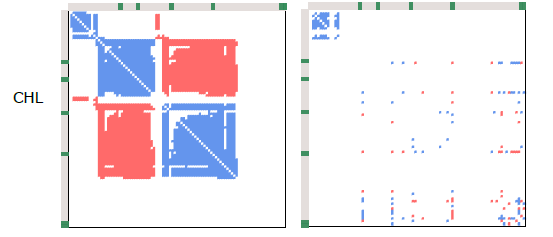

For the first time, we can now see the belowground implications of these heavily studied mountain roads. And the impact? Brutal. Roadside plots consistently showed a collapse in the complexity of plant-fungal and fungal-fungal co-occurrence networks – by 66–95% and 40–94% in total edge density, respectively. And yet, interestingly, fungal richness didn’t go down. Many of the key taxa were still present.

What this tells us is that the species are still there – just like aboveground, where we often see even more plant species in roadsides than in adjacent plots. But their networks are gone. Their roles, their interactions – the whole belowground social fabric – has unraveled. They’re in the roots, but they’re not doing what they’re supposed to be doing.

And in that ecological vacuum, the usual suspects step in: generalists like arbuscular mycorrhizae, who aren’t very picky about their plant partners, and pathogens with low host fidelity. They thrive. But more host-specific fungi – like ectomycorrhizae – don’t. Just like we saw in several of Jan Clavel’s PhD papers (e.g., here), those specialists don’t fare well in these unpredictable, human-altered environments.

Our takeaway? Road disturbance leaves a consistent negative imprint on the connectivity between plants and fungi. It’s a stark reminder that even systems with high species richness can be fundamentally unstable and vulnerable – especially when facing additional pressures like climate change and biological invasions.

So yes – please take the time to dive into this paper. We poured our hearts into it.

Reference: Radujkovic et al. (2025). Road Disturbance Shifts Root Fungal Symbiont Types and Reduces the Connectivity of Plant-Fungal Co-Occurrence Networks in Mountains. Molecular Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17771