Back in 2021, we had an important thought: maybe we should start treating microclimate the same way we treat macroclimate. Weather and climate are monitored by national governments through organized, standardized networks – so why not microclimate too?

We wrote a short note to get that idea out into the world. Nice, said the reviewer, but tell me more about the ‘how’! And so we did. We developed some R code to help people figure out where to place those sensors. Nice, said the reviewer again – and in the end, the paper became mostly about that.

Nice, said the readers, but what if we want to do this locally, not at the country level? We still have questions! We got talking, and soon a new idea was born:

👉 How do you set up your own microclimate network, even if you have as little as two sensors?

And that brings us to our new paper, just published in Ecological Informatics.

A flexible workflow for anyone

This new paper brings everything together. It includes:

- Even more flexible R code for site selection. You can work with a fixed budget, or let the code tell you exactly how many sensors are needed to cover your region.

- Guidance on project design from start to finish, so you don’t just know where to put sensors, but also how to structure the entire monitoring effort.

- A nice workflow diagram to guide you through all the steps — from defining your questions, to engaging the community, to placing sensors, analyzing data, and communicating results.

Why microclimate is different

Microclimate monitoring comes with some unique challenges. Covering the full variation in a landscape often means crossing human-made boundaries, which in turn means involving many landowners.

Take our large project in Flemish gardens: here, citizen science became essential. Thousands of people installed sensors in their own gardens, creating a network far beyond what we could have done alone.

To make things more concrete, the paper also walks you through three case studies from our own work:, from the forests of Madagascar, over the deserts of Oman, to the urban gardens of Belgium

Each shows, step by step, how specific microclimate questions shaped our decisions.

The toolbox

Of course, there is a reason this paper is in Ecological Informatics: the code. The heart of the paper is a set of tools that let you:

- Visualize variation in your landscape for key microclimate drivers.

- Identify optimal sensor locations to capture that variation.

The beauty is that landscapes differ wildly – but the decision-making process is the same everywhere. That’s what the workflow makes reproducible.

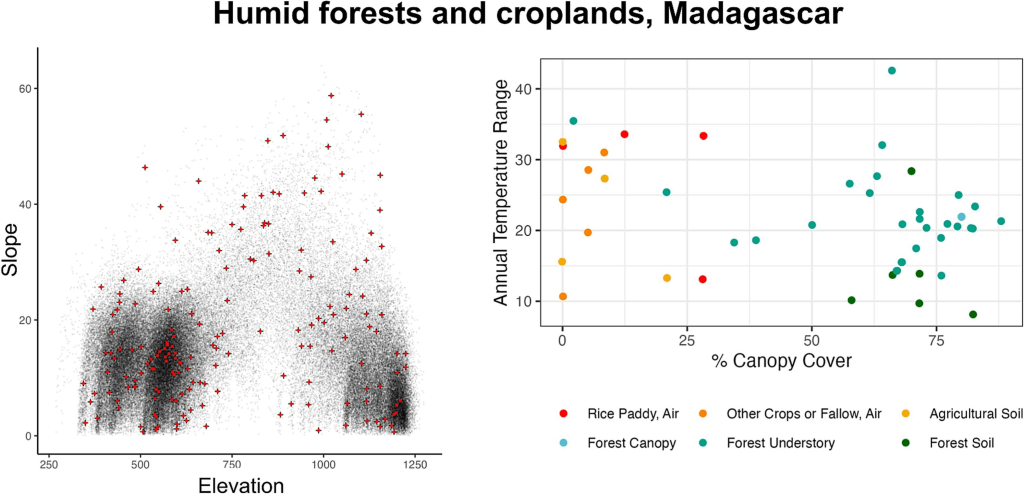

Take our case-study in Madagascar as an example. The region has two main plateaus, one at ~500 m and another at ~1100 m, connected by a steep slope. That slope, though small in area, is microclimatically quite important – so we had to oversample it. By contrast, the broad lowlands required fewer sensors, despite covering more space.

Then there’s canopy cover: ranging from 0 to nearly 90%. To capture that gradient properly, we spread sensors across both topographic and canopy variation.

This kind of exercise inevitably landed us in rice paddies and farmland – places with microclimates very different from forests (albeit surprisingly not so on this annual temperature range graph above). And that meant bringing farmers on board, motivating and involving them as part of the project.

In short, this paper is a step-by-step guide plus flexible R functions for anyone who wants to build a local microclimate network. Whether you have 2 sensors or 200, the workflow helps you design your network systematically, transparently, and with local context in mind.

We’d love to see this become a go-to resource for the growing community of microclimate enthusiasts. And of course—we’d be thrilled if the data from these networks feeds into the global Microclimate Database.

As for those nationwide microclimate networks? Governments haven’t yet picked up the urgency. But now you know about it too. And one day, we’ll make it happen.

References: