Non-native species have been widely studied for decades, and their affinity with urban environments is no surprise to anyone in the field. However, just how many non-native species dwell in our cities was so far unknown. With a global consortium of invasion ecologists, we set out to map this invasion in cities around the world – starting with a simple count of non-native species. The results are as impressive as they are concerning.

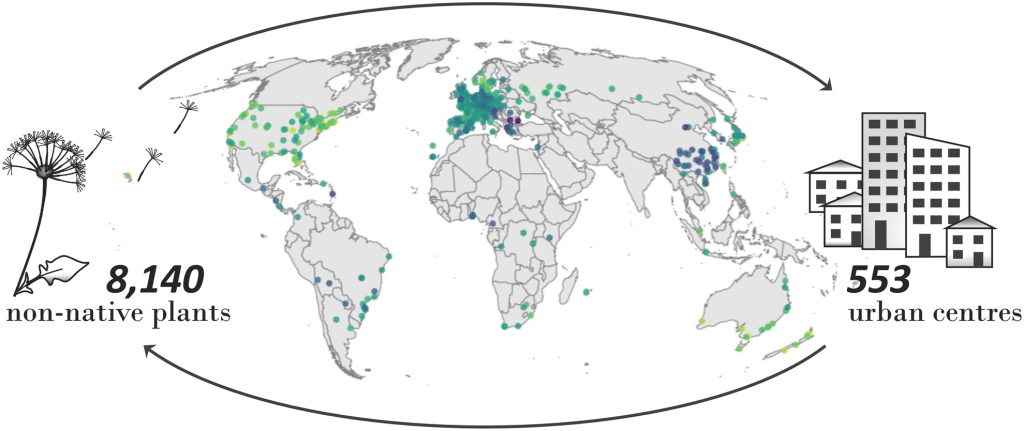

Our approach was straightforward enough: count the number of non-native plant species in various cities. By examining 61 countries, we obtained a clear snapshot of the impact non-native flora is having on urban environments. The full tally: 8140 species from 553 urban centres across the globe!

Numbers were particularly high in cities across the United States and Australia, while in Europe, London led the count. In the Netherlands – my new scientific home – we identified no fewer than 860 non-native species, ranking our country 15th among the 61 nations examined. However, it’s important to note that these figures reflect both the extent of invasion and variations in sampling intensity, so they should be interpreted with caution.

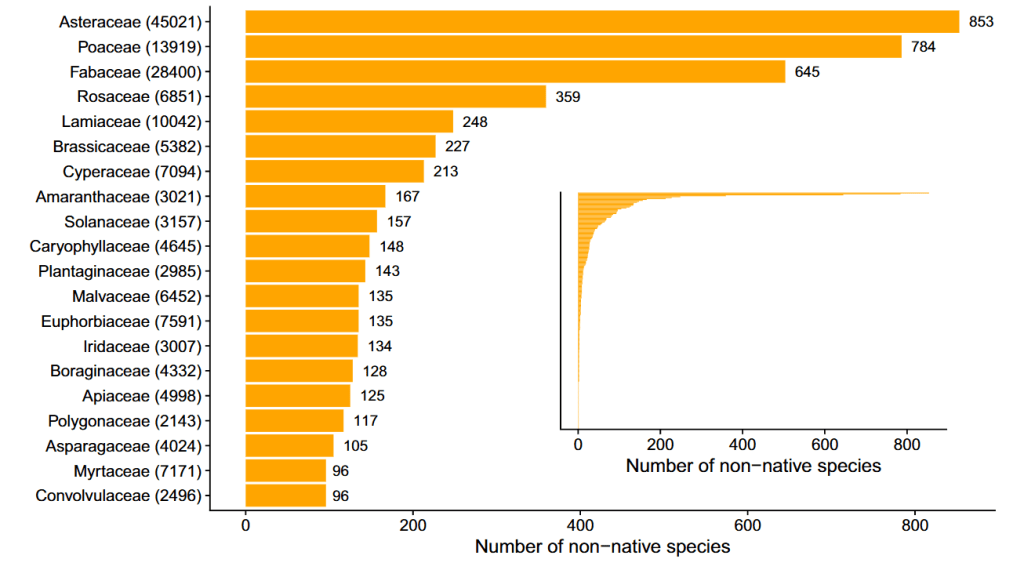

What is particularly interesting, however, is which species are leading the dance. The usual suspects, of course, with the overall record holder being the Canadian finebeam (Erigeron canadensis), a scrawny little thing of no apparent beauty that was found as a non-native in a mindboggling 469 cities across 47 countries. Its ability to thrive in diverse climates and urban settings is both fascinating and concerning.

Number 2? Veronica persica, still found in 41 countries. Exactly the reason why we studied its performance in urban settings in a previous paper!

What do these numbers mean for our cities? They provide valuable insights for urban policy while raising pressing questions about the resilience of our ecosystems. How will we manage the growing presence of non-native species, and what can we learn from the Canadian finebeam’s success?

Our new database paves the way for future studies and policy discussions. By mapping non-native plant invasions, it offers key data and tools for comparative assessments, hypothesis testing (like biotic resistance or invasion debt), and even modeling invasion dynamics. Ultimately, this resource supports informed decision-making in conservation, ecosystem restoration, and sustainable urban management.

Reference: Li et al. (2025) GUBIC: The global urban biological invasions compendium for plants. Ecological Solutions and Evidence. https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2688-8319.70020