I’ve always been intrigued by ecological scaling – it’s literally in my title: Assistant Professor in Ecological Scaling.

One of the main reasons we care so much about scaling is that ecological theories don’t always hold up when we change scales. What seems true in a single valley, forest plot, or mountain slope can fall apart when we zoom out to continents or the globe. That mismatch often gets us into trouble when trying to generalize from our favourite local case studies to something that has real global relevance.

A classic example: homogenisation

The theory goes like this: when ecosystems are invaded by non-native species, they start to look more and more alike. We call this biotic homogenisation – a reduction in beta diversity, meaning less variation among communities. It’s often linked to lower ecosystem functioning, and by extension, poorer ecosystem health.

So far, so simple. Except the evidence is a little bit messy. Some studies find strong homogenisation, others don’t. We suspected that part of this inconsistency comes from differences in spatial scale – not all studies are asking the same question in the same “ecological zoom level.”

Scaling up with global replication

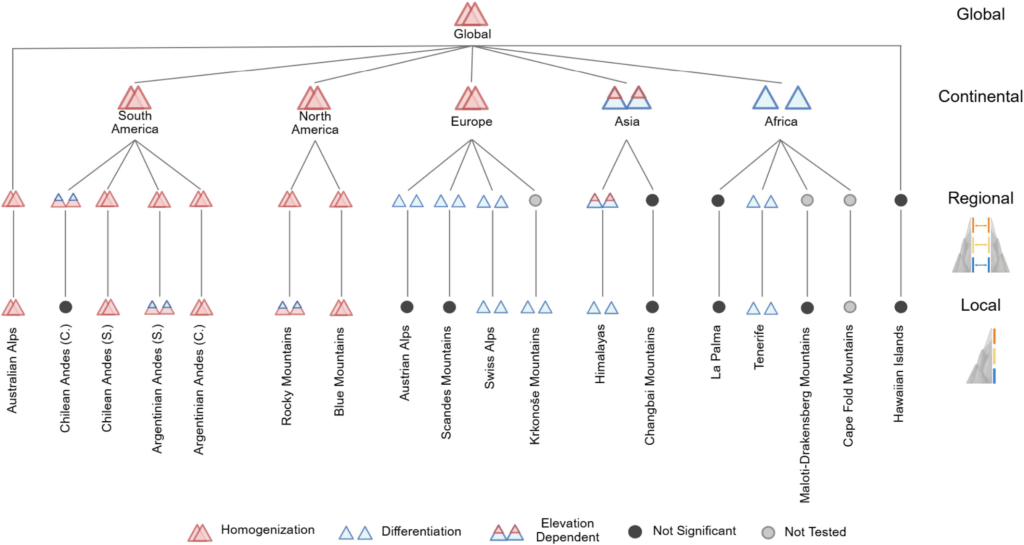

To test this idea, we turned to one of our favourite tools: globally replicated monitoring. Thanks to the Mountain Invasion Research Network (MIREN), we could explore patterns of homogenisation – and its opposite, differentiation – across 18 mountain regions worldwide. The findings of this exercise – led by Meike Buhaly – are now published in Global Ecology and Biogeography.

Our hypothesis (perhaps a bit naively in retrospect) was that homogenisation would dominate across all scales, though we expected it to weaken with elevation.

Yet that was, surprise surprise, not what we found. At the global scale, the classic theory held neatly: non-native species homogenized communities. Plant assemblages across continents became more similar (lower beta diversity) once non-natives were included. But when we zoomed in, the pattern fell apart. At local and regional scales, homogenisation and differentiation were almost evenly balanced. And even more intriguingly, the pattern split along continental lines:

- In the New World (the Americas and Australia), homogenisation dominated.

- In the Old World (Europe, Asia, Africa), differentiation was more common.

The pattern depends on where (and how far) you look

In the New World, we found consistent homogenisation across local to continental scales, particularly in lowland plant communities. This likely reflects both the high number and shared history of non-native species: many are widespread across entire continents, occurring in more plots than native species.

At higher elevations, however, in some regions this pattern reversed. When non-native species became rare and patchy, this lead to community differentiation instead, especially in the Andes and Rocky Mountains.

The Eurasian mountains told a different story. There, non-native species actually caused differentiation at local and regional scales, even though some were shared across regions. At the continental scale, these same shared species produced a faint signature of homogenisation, but much weaker than in the New World.

The consistent differentiation we found in Eurasia might simply reflect an earlier invasion stage. With fewer non-native species and fewer widespread invaders, communities still differ strongly from one another. But as non-native species continue to spread, homogenisation may increase into conditions that mirror what we already see in the Americas and Australia.

Scaling reveals nuance – again

So, as so often in ecology, the story depends on scale.

At large, continental scales, non-native species clearly homogenize plant communities: ecosystems across continents begin to share the same species. But when you zoom in, that signal becomes patchy. Homogenisation dominates in regions with long invasion histories, while newer invasion fronts still show differentiation.

It’s a pattern that fits a familiar ecological theme:

a little change might be positive – but a lot can be profoundly transformative.

More information: Buhaly et al. (2025). Global Homogenisation of Plant Communities Along Mountain Roads by Non-Native Species Despite Mixed Effects at Smaller Scales. Global Ecology & Biogeography. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.70137