Oftentimes the simplest scientific methods hide a whole iceberg of complexity. The Tea Bag Index (TBI) is no exception. On the face of it, it’s brilliantly straightforward: bury some green and rooibos Lipton tea bags, dig them up after about 90 days, and compare how much they’ve decomposed. What could be easier?

Well… as always in science, a lot, actually.

Our recent paper in Ecology Letters, based on a whopping 36,000 tea bags, sparked some healthy scientific debate. In a follow-up response to critiques by Mori (2025), we now dove deeper into the assumptions behind the TBI and clarified what this method can and cannot tell us.

At its core, the TBI is designed to give everyone – from scientists to students and citizen scientists – an accessible way to study decomposition across environments. It does this by estimating two key values:

- S_TBI: how much material resists decomposition (a stabilisation factor)

- k_TBI: how quickly decomposition starts (an initial rate)

The method’s strength lies in its simplicity and global standardisation. It allows us to compare results across locations and climates without the messy variation of local litter types. That makes it incredibly useful for large-scale studies. But because it’s such a simplification of the real world, it’s important to use it with care.

What the TBI tells us – and what it doesn’t

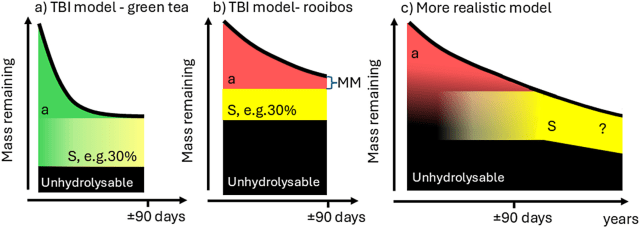

Plant material, including tea, breaks down in stages. Some parts go fast, others hang around for years. The TBI focuses on the early, fast stage, but in the real world, the slow stuff might start decomposing earlier than assumed. So, while the TBI gives us a valuable snapshot of early decomposition, it doesn’t reflect the full timeline of what happens to organic matter in soil.

Rethinking the assumptions

The TBI assumes that 90 days is enough for green tea to reach a stabilised phase (so you can measure S_TBI) and that rooibos tea is still in its early phase (so you can measure k_TBI). Our data confirm that green tea generally fits this assumption well. Rooibos tea, however, shows more variation – and that variation isn’t always easy to explain.

Another assumption is that we can use green tea’s stabilisation factor to estimate that of rooibos tea. But our findings show that the predicted stabilisation (S_TBI) doesn’t always match what’s actually observed in long-term rooibos data. In fact, applying S_TBI early on might inflate k_TBI. However, since k_TBI tends to underestimate actual decomposition rates (k_real), this may not be a major issue.

So, what can we trust?

Despite its imperfections, the Tea Bag Index remains a valuable tool. It captures short-term decomposition well and enables comparisons across environments by using a consistent material. It’s not meant to replace more detailed, site-specific studies – it’s meant to complement them.

For future work, we suggest treating the two TBI parameters – k and S – as distinct components shaped by different environmental drivers. Combining TBI results with chemical analyses and longer-term studies could help bridge the gap between simplicity and ecological realism.

In the end, the Tea Bag Index doesn’t capture the whole story of decomposition – but it does capture a really useful chapter. And sometimes, that’s exactly what you need.