New paper: Reynaert et al. (2023) Direct and higher-order interactions in plant communities under increasing weather persistence. Oikos

Let’s knock down an open door: interactions between species are key determinants of their performance. How well an individual is growing, or even if it is growing somewhere at all, hinges significantly on the surrounding organisms. They may vie for vital resources like air or sunlight, or conversely, aid one another by providing shade against the scorching rays of summer.

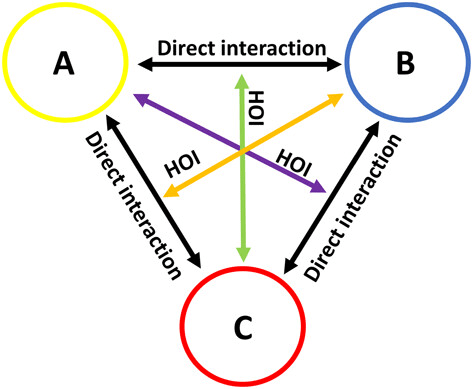

It should therefore not come as a surprise that there are thousands of papers on biotic interactions and their role in ecosystem functioning. However, while we have learned a lot about this over the last decades, there is still a surprisingly big hole in that literature. And that gaping hole is the result of inevitable oversimplification. That is, we have way too often – for the sake of simply being able to grasp ecology’s complexity – limited ourselves to direct interactions: A outcompetes B, C facilitates D. Yet, natural interactions seldom adhere to such straightforward narratives. Within an ecosystem, every individual is engaged—albeit to varying degrees—in an intricate dance of relationships, influencing and being influenced in turn.

Consider, for example, a scenario where a plant species, Plant A, attracts a specific herbivorous insect. Ordinarily, these herbivores might feed on Plant A, reducing its fitness. However, another plant species, Plant B, grows nearby and emits a molecule that attracts predators of the insects. As such, Plant B is indirectly helped by Plant A, as Insect B comes to eat Insect A. Or any other orientation of interactions.

These intricate and multifaceted relationships are labeled higher-order interactions (HOIs), a domain that has consumed a considerable amount of my time to get a hold of them in a convincing, statistically sound way. In a first attempt, we used real-world data from our mountain vegetation monitoring initiative (MIREN, http://www.mountaininvasions.org). However, that turned out very tricky, as there were simply way too many things changing at the same time to isolate something as complex as these higher-order interactions. After many an attempt, that idea was moved to the ‘death paper pile’.

In a new attempt, however, expertly led by UAntwerp-colleague Simon Reynaert and now published in Oikos, we took a different turn. We made use of a fascinating controlled experiment performed at our university campus, where precipitation was manipulated for 256 so-called mesocosms (in essence: pots with plants). What made this experiment especially useful was the uniform conditions experienced by all plants and pots, with precipitation being the sole variable—specifically, not even the AMOUNT, but the timing of rainfall.

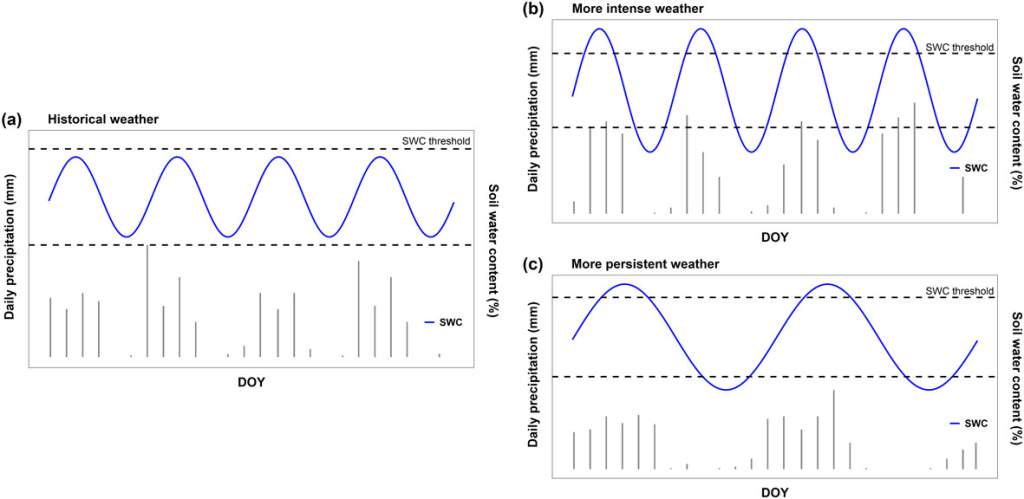

An explanatory framework illustrating how changes in rainfall patterns, specifically increased variability, can impact the moisture levels in the soil. The grey bars represent daily rainfall amounts. Across all panels, the total precipitation matches historical weather averages (a).

When weather becomes more intense (b), it leads to less frequent but heavier rainfall episodes interspersed with extended periods of dryness, particularly during higher temperatures. This scenario could worsen the effects of droughts or floods.

On the other hand, when weather patterns become more persistent (c), it results in prolonged stretches of both dryness and wetness. This persistence might intensify the fluctuations in soil moisture content, potentially causing more extreme variations.

In both scenarios, there’s an increased likelihood of surpassing critical soil moisture levels. This excess—either too much or too little moisture—can detrimentally impact how ecosystems function.

By holding all these conditions constant, except for the precipitation regime, we could finally test how extreme events affect HOIs. And yes, lo and behold, our results indicate that species interactions (including HOIs) are an important determinant of plant performance under this increasing weather persistence. Moreover, the importance of these interactions changed substantially along the gradient of weather persistence, with HOIs showing a shift towards stronger facilitation (or weaker competition) as drought persistence increased.

What was thus interesting, was that HOIs – at least partially – counteracted the effects of direct competition by neighbours, a conclusion that has been made in other studies as well. This could mean good news for biodiversity, as complex interactions could as such help support a higher diversity. However, a cautionary note is necessary: this counteractive effect was truly only partial, and could not overcome the increased drought intensity experienced in the most extreme precipitation regimes. In the end, species succumbed on their own to the extreme drought, and no positive higher-order interaction effect could prevent that from happening.

There was a lot more to the results, of course, with perhaps the main conclusion that, indeed, HOIs are bloody complicated to analyze statistically. Even in this extremely controlled setting, picking up on these trends remained difficult. Thus, while ample papers have shown the theoretical importance of HOIs, we are still a long way from routineously integrating these complexities in our ecological analyses.