It was summer 2017, the height of my PhD. As always, I spent the longest days above the polar circle, in the north of Scandinavia. We were there to follow up on our long-term vegetation monitoring, in particular this time to do the five-year resurvey of the roads we are tracking there for the Mountain Invasion Research Network. Little did we know that amidst all the data collection, a side project involving leaf harvesting would eventually lead us on an unexpected journey.

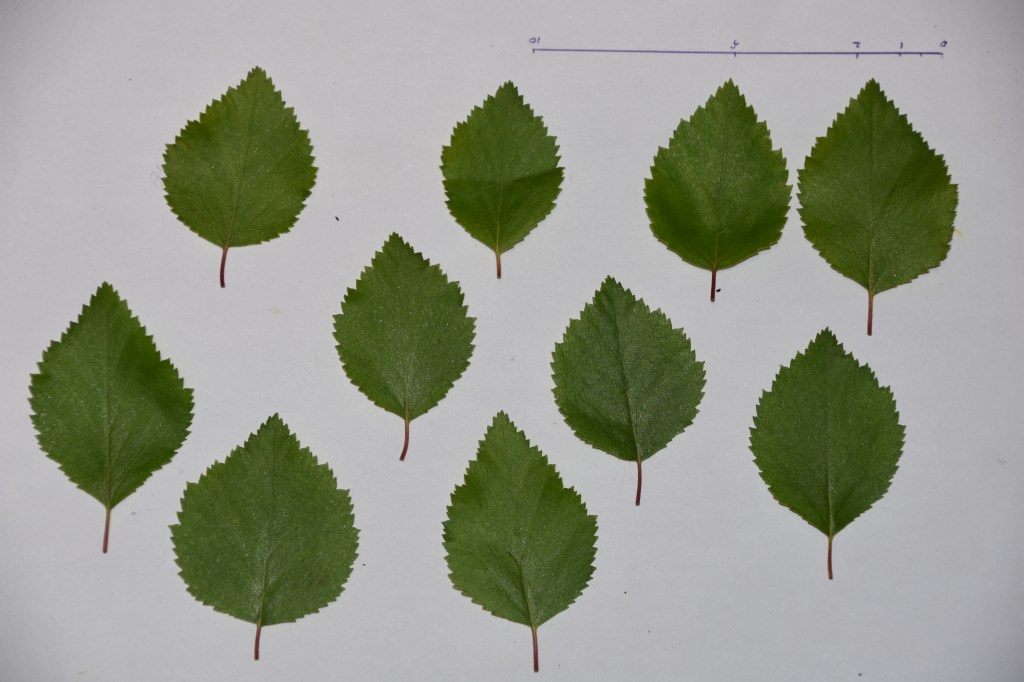

We also harvested a bunch of leaves, that summer. Our goal? To examine plant traits across various elevations and explore the impact of roadside disturbance on these traits. Our dedicated master student, Amélie, crafted a fascinating thesis, full of intriguing discoveries that unfortunately remained buried in the shadows, as so far too often the case with master theses.

However, our leafy escapades did not go in vain. We decided to contribute our precious data to the Tundra Trait Team-database, led by the indomitable Anne Bjorkman from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, making them a vital building block for a global dataset of tundra plant traits.

Now, that global database has resulted in a new and exciting study, freshly published in Nature Communications. The idea was to combine this large database with species distribution data, and hopefully predict which species would emerge as champions or casualties in the increasingly-changing climate of the tundra. The hypothesis was that it would, as one can expect certain kind of species – with certain traits – to benefit disproportionally more or less from changing climatic conditions in the tundra than others. For example, all signs point into the direction that taller plants would increase significantly in cover at the expense of short-stature ones.

Now, was that a bit of a disappointment! Our initial hypothesis, built upon the pillars of previous literature, proved too simplistic for the complex world of tundra shrubs. Instead of consistent trait responses, we discovered similar values of height, specific leaf area, and seed mass among both range-expanding and contracting tundra shrub species. Mother Nature is known to love her surprises!

Importantly, projected range shifts will thus not lead to directional shifts in shrub trait composition or variation, as both winner and loser species share relatively similar traits.

As usual, of course, there is plenty of room for improvement. Our study highlights the need to explore other morpho-physiological traits for which sufficient data remains elusive, and to address how demographic processes might mediate tundra shrub range shifts.

In our quest to uncover the future winners and losers of climate change in the mesmerizing tundra biome, we’ve encountered a few unexpected twists and turns. It’s as if these plants are whispering, “Don’t judge a shrub by its leaves!” The observed and projected abundance changes and range shifts will thus interestingly enough not lead to major modifications in shrub trait composition, since winner and loser species share relatively similar traits. So, as a scientist, I’m happy to shout out as a conclusion: “oh boy, is it complicated!”