Dark diversity. A term that sounds sufficiently dramatic to catch the attention of many an ecologist. But it’s a good theory as well to explore: instead of the common ‘diversity’, which looks at the diversity of species/genes/traits present at a certain location or in a certain region, dark diversity focuses on those species that are NOT there. Even more importantly, it focuses on those species that are not there, but SHOULD have BEEN there. The hidden masses, the forgotten ones, those that have been lost.

The field of dark diversity tries to explain why certain species are not where they should be, in the hopes that this can give us a better understanding of community dynamics, and risks for biodiversity loss.

Intrigued? We were too, so we decided to estimate the dark diversity of our study region in northern Scandinavia, in the area surrounding the Abisko Research Station, as part of DarkDivNet, the dark diversity network. That work – led by master’s student Lore Hostens – now got published (here)!

We got to work by monitoring the species that were present, and then scanned the literature for different methods to estimate dark diversity based on those. That’s when things starting to go dark (pun intended). Indeed, there were important decisions to take: which method to choose? There were a whole bunch available, many of them with several additions, adjustments, or nuances around them.

Would it matter which method we chose? Now, YES, it would! Soon enough, this question grew into our main research question: how much did the outcome differ between the different dark diversity estimation methods? Would conclusions still hold when switching from method A to B? Brace yourselves, as we are entering the muddy terrain of incomparable indices.

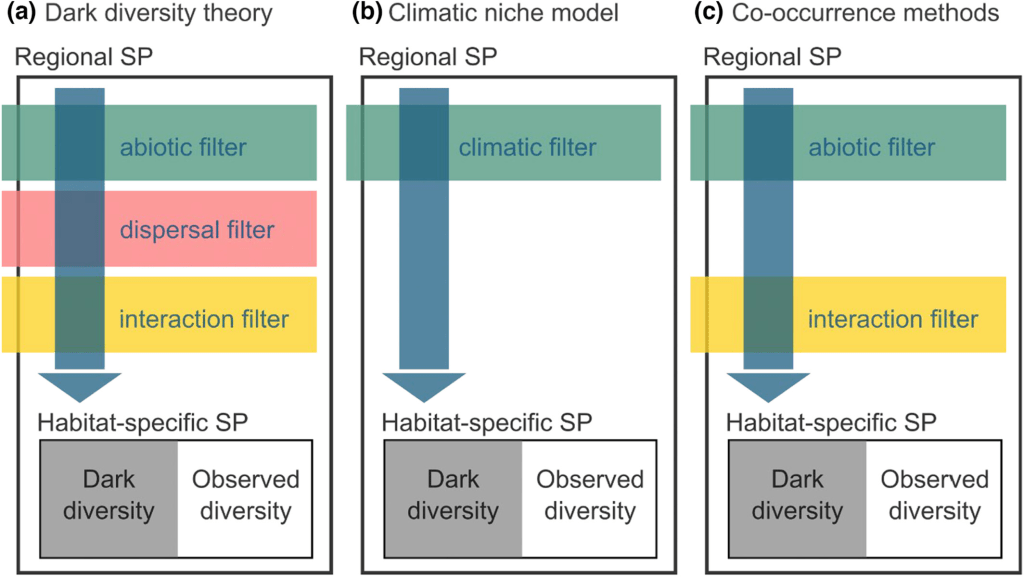

Basically, there are (at least) three main methods to estimate dark diversity, depending on what filters one incorporates to estimate which species should and should not be present at a site. These are summarized in the figure above. Theoretically, one would exclude all species that 1) cannot occur there due to a mismatch in their environmental niche (too cold, too warm, too acid…), 2) cannot occur there because they can’t reach the place (too far away), and 3) those that are outcompeted by other species at the site (too weak, or incompatible). Unfortunately, every method has a different way of dealing with those filters.

So, many of these dark diversity estimates are theoretically substantially different. What is more, even when choosing a certain path, there are still a myriad of decisions one has to take that could affect the outcome. It should thus come as no surprise that in our case study, conclusions were entirely overturned by switching from one method to the other.

The why and how of these differences are explained in detail in the paper, which you can find here.

In this story, I just want to ensure that you take one lesson home from this, and that’s the following: the concept of dark diversity is very intriguing, and intuitively makes a lot of sense, but be extremely wary of the methodological decisions that underlie it. If you use just one method to estimate your dark diversity, you might be building your conclusions entirely on loose sand. What’s more, I wouldn’t be surprised if these cautionary words could not be expanded to many other concepts in ecology that are supported by mathematical indices. Your index only tells you exactly what it measures, nothing more and nothing less, and the decisions you make along the way can have fundamental effects on your outcomes. So please, stay wary of the mathematics underneath your ecology, as they are more important than you might wish!

Note: we are no statisticians. We are humble ecologists enthusiastically coming into a problem and ending up in the mud, and just want to warn others not to get stuck!