Scientific research often presents itself as a search for truth—rigorous, objective, and driven by data. But what if the same dataset, analyzed by different researchers, leads to different conclusions? That’s exactly what happened when a group of ecologists, including myself, took part in an ambitious experiment. An experiment in which we ourselves – the ecologists – were the test subjects. Our main goal? Testing the reproducibility of ecological data analysis. The results are now out in BMC Biology, and they are as fascinating as they were humbling.

A team effort in data exploration

I joined this project as an opportunity for my students to together learn how best to apply statistical models to real-world ecological datasets, taking it on as a collaborative activity with The 3D Lab. The premise was simple: multiple research teams around the world would analyze the same dataset, aiming to answer the same research question. It was an exciting challenge—what patterns would we uncover? How would our results compare to those of others?The hypothesis being, of course, that whoever analyzed the dataset should come to the same conclusion. There are scientific truths behind such data, right? Right?

The two datasets

The study focused on two different ecological questions:

- Blue tits – Does the number of young birds in a nest affect their growth?

- Eucalyptus seedlings – Is there a relationship between the number of seedlings in a plot and the proportion of grass cover?

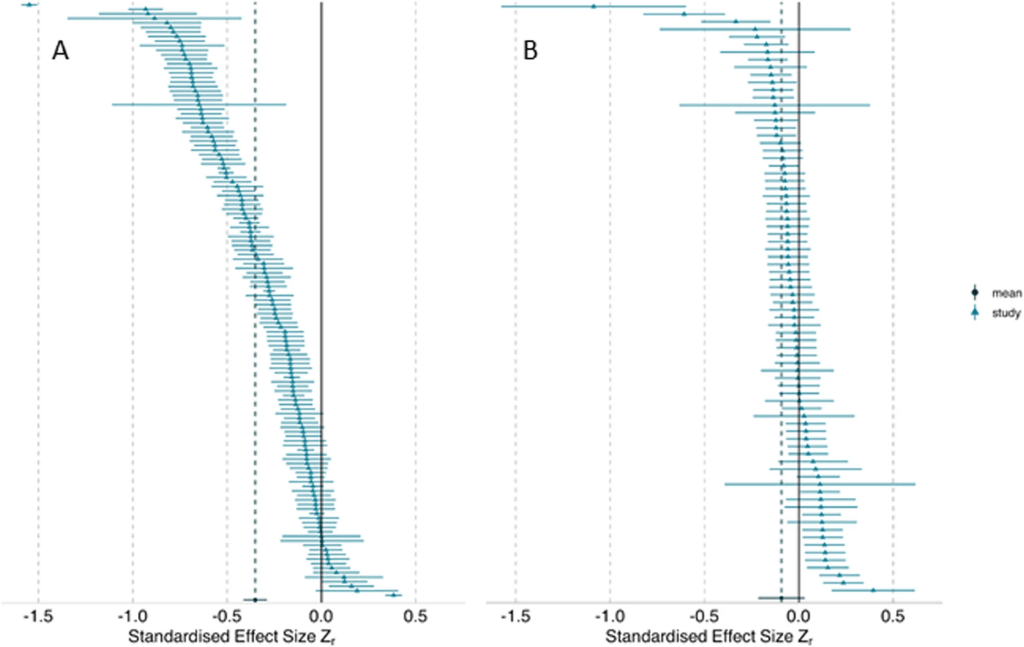

Our The 3D Lab-team dove into the dataset of the Eucalyptus seedlings – the trickiest one of the two. The blue tit dataset was relatively straightforward. Most researchers identified a negative correlation—young birds grew less when they had more siblings. However, here we had it already: there was significant variation in the strength of the correlation, and a few researchers even found a positive relationship!

The eucalyptus dataset was an even messier affair. While the overall pattern suggested only a weak relationship between seedlings and grass cover, a third of the researchers found either a positive or negative correlation. Some even identified strong relationships in opposite directions. These inconsistencies highlight a critical issue: the methods we choose can significantly shape the results we get.

Why do results differ?

At first glance, these discrepancies might seem alarming. But they are not necessarily a sign that ecologists are bad at statistics – although that could contribute to it. Instead, they reflect the complexity of ecological data. Nature is noisy—environmental variables interact in intricate ways, making it difficult to draw clear-cut conclusions.

Importantly – in support of us statististicing ecologists, the study also found that researchers who reached unusual conclusions did not necessarily make methodological errors. We did indeed find substantial variation in the variable selection and random effects structures among analyses, as well as in the ratings of the analytical methods by independent peer reviewers, but we found no strong relationship between any of these and deviation from the meta-analytic mean (i.e., likely ‘wrongness’ of the analysis). This suggests that small choices—such as selecting a particular statistical test or data transformation—can have a big impact on the final conclusions.

What can we learn from this?

One of the biggest takeaways from this study is that statistics is not a magic wand. While it is a powerful tool, it does not eliminate uncertainty. This means that, as ecologists, I believe we should be more open about the limitations of our analyses and avoid blindly chasing statistical significance. The common threshold of p < 0.05 should not be treated as the sole indicator of truth.

Instead, robust research relies on multiple approaches:

- Replication – The more times an effect is observed, the more confidence we can have in it.

- Different methods – If different analytical techniques point in the same direction, the pattern is more likely to be real.

- Transparency – Clearly documenting our choices helps others understand how we arrived at our conclusions.

Staying critical – even (or especially) of our own work

Personally for me, this study served as a reminder to stay critical of my own results. It’s easy to get excited when we find a nice correlation, but are we considering the full range of possible interpretations? Couldn’t we have made a series of equally-valid other methodological decisions, and what would have happened to our results then? Since participating in this project, I’ve made a habit of as much as possible explicitly acknowledging uncertainties in my papers. Perhaps more importantly, even, I now always use this example in my teaching, encouraging students to think about how different analyses can lead to different outcomes. Now there first statistical model they make as part of my team is one using the messy Eucalyptus dataset, showing them how we can in good consciousness report about the weak correlation in there.

Ecology is a science of patterns, processes, and probabilities. While we may never achieve absolute certainty, recognizing the sources of variability in our analyses makes us better scientists. And perhaps, a little more humble along the way.

Reference: Gould, E., Fraser, H.S., Parker, T.H. et al. Same data, different analysts: variation in effect sizes due to analytical decisions in ecology and evolutionary biology. BMC Biol 23, 35 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-024-02101-x

PS: note that this manuscript was published as a ‘registered report’, which means that it is a peer-reviewed research article from which study plans, including hypotheses and methods, were reviewed and accepted before the actual work was done, ensuring transparency and reducing publication bias. Pretty cool, huh!